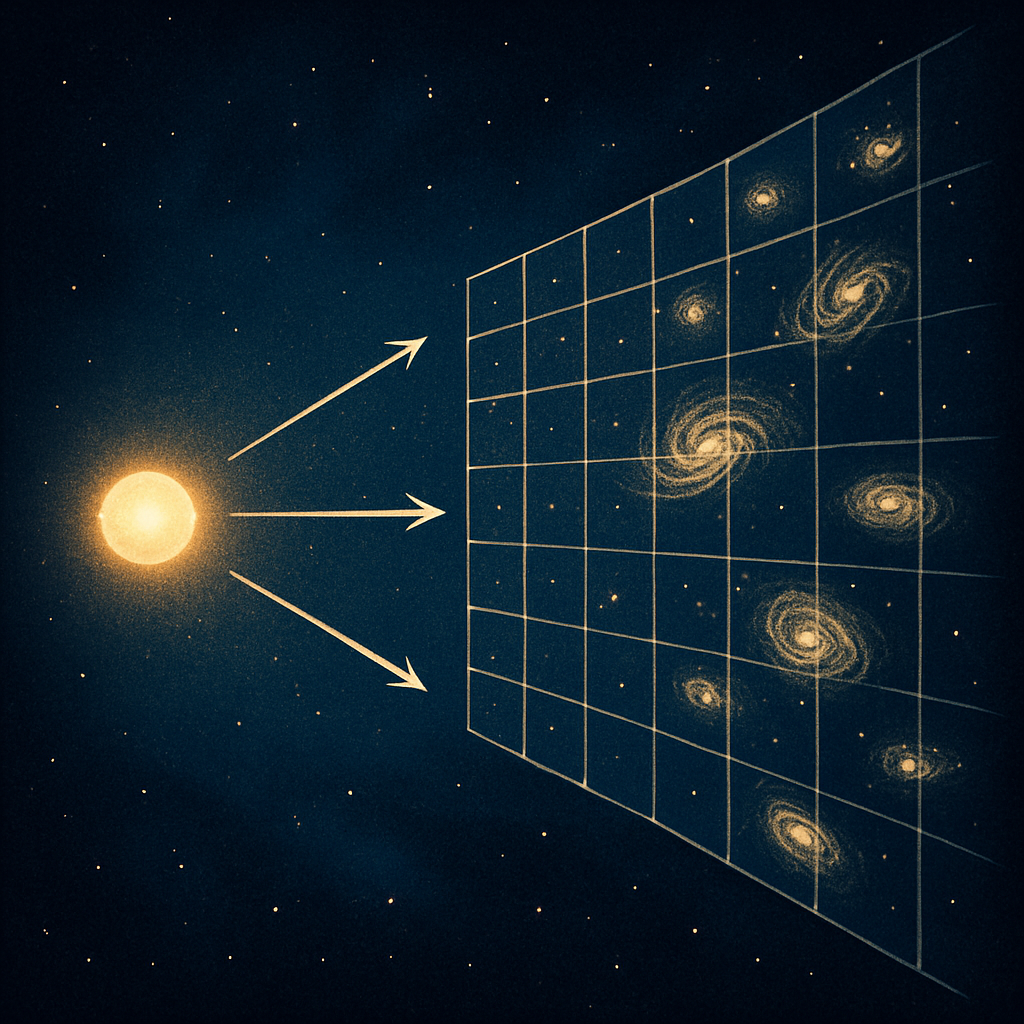

Modern physics treats light as an electromagnetic wave and particle that always moves at the same high speed in vacuum. By definition c=299,792,458 m/s, and all forms of electromagnetic radiation (including visible light) travel at this speed in empty space[1][2]. This invariance of c is a cornerstone of Einstein’s theory of relativity, which says that all observers, regardless of their state of motion, measure the same light speed[1]. In practice, this means that when we look at distant stars and galaxies, we see light that has traveled for many years before reaching us; for example, light from our Sun takes about 8 minutes to arrive at Earth, and light from a galaxy 400 million light-years away is 400 million years “old” by the time we see it[3][2]. In this way, astronomical observations let us study the distant past of the universe. However, this picture relies on several theoretical assumptions about light and space.

Foundational Assumptions in Light Theory

Two key assumptions underlie modern light theory and relativity:

- Constancy of the speed of light (c): Physics assumes c is the same for all observers and does not change over time or with distance[1]. This is built into how we define meters and seconds, so today c is an exact defined constant[1].

- Inertial reference frames: Relativity uses idealized “inertial frames” (non-accelerating coordinate systems) in which the laws of physics take their simplest form. It is assumed such frames exist (at least locally) and that no frame is preferred (no “absolute” rest)[4]. This leads to the principle of relativity: the laws of physics (including light’s behavior) are the same in any inertial frame.

These assumptions form a layered logical structure. For example, we assume there is no fixed “aether” medium for light (because experiments like Michelson–Morley found no evidence of it[5]). From this follows Einstein’s postulate that the vacuum itself behaves the same for all observers and that light’s speed is constant. Combined with the symmetry of spacetime, this leads to the relativistic equations (Lorentz transformations) that let us compute distances, times, and velocities consistently for moving observers[1][4].

Why These Assumptions Matter in Cosmology

These assumptions are crucial for measuring cosmic distances and ages. For instance, astronomers use Hubble’s law to estimate how far galaxies are: they measure the redshift of a galaxy’s light (the change in frequency caused by cosmic expansion) and convert it to a recession velocity. Because we take the speed of light c as fixed, the velocity v and distance d are related v≈H_0 d (with H_0 the Hubble constant)[6]. In practice, a higher redshift means a faster recession and thus greater distance, assuming constant c. NASA explains that “from a measurement of the red shift and the [Hubble] constant…, astronomers can determine the distance to a galaxy”[6]. Similarly, our estimates of the universe’s age (e.g. “13.8 billion years since the Big Bang”) rely on how long light has been traveling to reach us. These calculations all rest on assuming the one-way speed of light is constant and that we can synchronize clocks across space.

Likewise, time ordering of events depends on these assumptions. Because light takes time to reach us, we always see celestial objects as they were in the past. As NASA notes, “the finite speed of light means that we must always be out of date” – for example, we see the Sun as it was 8 minutes ago, and a galaxy 400 million light-years away as it was 400 million years ago[3]. In general relativity, effects such as the bending of light by gravity (gravitational lensing) and the expansion of space modify how we interpret these distances and times. But fundamentally, our cosmic clocks are set by light travel at speed c. If c is not truly constant or if light’s path is altered, our distance/time calculations could be off.

Challenges to Testing the Assumptions

Importantly, several of these assumptions cannot be tested directly. For example, we assume perfect inertial frames exist, but on Earth and in the cosmos we always have some acceleration or gravity. No perfectly isolated inertial frame can be realized in practice. Similarly, the one-way speed of light cannot be measured independently. As physicists note, determining the one-way speed (from a source to a distant clock) requires already synchronized clocks at two locations. But synchronizing spatially separated clocks itself assumes a definition of simultaneity tied to the speed of light[4]. In other words, one must conventionally set the one-way light speed to be c in order to sync clocks, so experiments can only ever verify the two-way (round-trip) speed of light. Wikipedia explains that the one-way speed “cannot be measured independently of a convention as to how to synchronize distant clocks”[4]. All high-precision tests (like Michelson–Morley and others) have only confirmed that the average round-trip speed is [4][7].

Moreover, Earth is not an ideal inertial frame: it rotates and orbits the Sun, and is subject to gravity. Thus, every real experiment occurs in a non-inertial context. We assume that effects of these can be factored out, but it is an assumption. For example, the famous Michelson–Morley experiment was done on Earth in a gravitational field; we assume this did not invalidate its null result. Similarly, we assume light’s speed is constant everywhere in the universe. But in general relativity, light can be slowed or redshifted by gravity or the expansion of space. We must assume (or define) how clocks and rulers work at distant locations. These untestable conventions underline that our picture of light in the universe is partly shaped by theory.

Reassessing Historical Experiments

The classic experiments on light’s speed deserve scrutiny. Michelson and Morley expected to detect an “aether wind” from Earth’s motion through a medium; instead they found no significant fringe shift. This is often cited as evidence that light’s speed is isotropic (same in all directions). However, detailed analyses point out that what was actually measured was the round-trip (two-way) speed. Recent studies note that Michelson–Morley and similar interferometer tests “only confirmed that the average velocity of light is constant and equal to [8],” not that the instantaneous one-way speed is constant in all directions. In fact, a 2019 analysis explicitly states: “We have shown that [Michelson–Morley] does not imply that the current velocity of light is constant in every direction. The average velocity of light is constant and equal to

”[9]. In other words, these experiments ensured that light’s round-trip speed is

, but they leave room for anisotropy in one-way travel (as long as it averages out). The same authors remark that every repetition of Michelson–Morley (and related experiments like Kennedy–Thorndike) only ever verified this round-trip constancy[8]. Their conclusion: “Many theories in accordance with [the experiments] are possible” – the data do not uniquely force Einstein’s one-way postulate[8].

In addition, modern experiments continue to test light’s speed with higher precision, but always under the umbrella of synchronization conventions. For instance, in 2009 an optical resonator experiment still found “the absence of any aether wind” to one part in 10^17, but again this only confirms round-trip isotropy[10]. Other tests (Ives–Stilwell, etc.) support relativity’s predictions, but none circumvent the clock-synchronization issue. Thus, strictly speaking, experiments show no conflict with relativity, but they do not prove the assumption of absolute one-way constancy. They rely on and reinforce the conventional choice of how we define “simultaneous” events at a distance. This subtlety is often glossed over when teaching relativity, but it highlights that some foundational premises about light are, in practice, conventions or definitions built into the theory[4][9].

Implications for Cosmological Measurements

Because of these layers of assumption, our cosmological conclusions have built-in uncertainty. Distance estimates (like using supernovae or parallax) assume light has traveled at c along the way. Ages of stars or galaxies rely on light travel time. Yet if, hypothetically, the one-way speed were slightly different in different directions, or if clocks synced differently, our derived distances and ages could shift. Additionally, general relativity tells us that gravity bends light. NASA notes that massive objects like black holes can bend and distort light from more distant objects – a phenomenon called gravitational lensing[11]. In practical terms, light from a background galaxy passing near a black hole will take a curved path and arrive later than if space were flat.

This NASA artist concept shows a black hole bending light from its accretion disk. As NASA explains, a black hole’s gravity “bends light from the far side of the disk, making it appear to wrap above and below the black hole”[11]. In other words, light does not always travel in straight lines in the universe, and its travel time can be affected by gravity.

Because of such effects, any calculation of “look-back time” can be complicated. Light from a very distant supernova might skirt around an intervening mass or pass through gravitational wells, delaying it. If we are unaware of these paths, we may misinterpret the distance. Similarly, cosmic expansion stretches light’s wavelength, which we interpret as age and velocity (redshift). All these inferences assume general relativity is exactly correct and that we have modeled gravitational fields correctly. But dark matter, dark energy, and inhomogeneities mean our models still have uncertainties. In summary, if the fundamental assumptions about light’s propagation or the structure of spacetime are even slightly off, our cosmic distance ladder (and thus the universe’s timeline) could shift.

Another implication: we can never directly observe the instantaneous universe – we always see the past. The Chandra X-ray center illustrates that for a galaxy 400 million light-years away (NGC 6240), “our information… is 400 million years out of date”[3]. So the “now” we see on Earth is inherently delayed for distant objects. The deeper into space we look, the further back in time we see. This is physically true under finite c. However, if there were any mechanism (say, a cosmic speedup of light, or a cyclical time reset) that changed the relationship between distance and time, we might only ever glimpse a limited epoch. As Einstein famously said, “The past, present and future are only illusions, even if stubborn ones”[12] – a poetic reminder that our observations are bound by how light travels to us.

Unproven Theories and Open Questions

Modern physics acknowledges that many deep questions remain unresolved. For example, as one review of unsolved problems lists, we still do not know the nature of dark matter or dark energy, the exact mass of neutrinos, why matter vastly outweighs antimatter, or how to unify general relativity with quantum mechanics[13]. The Standard Model of particle physics itself is mathematically inconsistent with general relativity under extreme conditions like the Big Bang or black hole cores[14]. In cosmology, even the widely-accepted inflationary theory has mysteries: what is the inflation field, and are there alternatives? The same source notes that some scientists have explored variable-speed-of-light (VSL) theories as an alternative explanation to problems like the horizon problem[15]. These ideas are speculative, but they highlight that the assumption of constant c is not an absolutely rock-solid given—it is a choice that makes our equations work. In fact, critiques of VSL emphasize that changing c would require rewriting much of physics[16], which is why such ideas remain fringe. Nevertheless, the very existence of these debates shows that physics has not proven every possibility wrong.

Likewise, thought experiments like wormholes or closed timelike curves (time travel) arise from relativity’s equations, even if we suspect some “chronology protection” will forbid them. String theory and quantum gravity research aim to test how light and spacetime behave at the smallest scales, but no experiment has yet confirmed the final truth. Even measuring c itself is now a definition: since 1983 the meter is defined by how far light travels in a set fraction of a second[4], so we no longer “measure” empirically. Thus, one could argue we cannot, by any finite set of experiments, conclusively prove that c has always been constant everywhere in space and time. It is taken as a postulate that works extremely well for making predictions and giving consistency to our models.

Brahma Kumaris’ Cyclic-Time Perspective

Given these uncertainties, some spiritual traditions interpret cosmic history differently. The Brahma Kumaris (BK) teach that time is cyclic, not linear, with a full “World Drama” cycle of 5,000 years[17]. In BK doctrine, history repeats through four ages (yugas) of 1,250 years each[18][17]. For example, BK literature states: “The Full-cycle is shown to be 5000 years in which 4 distinct Ages are mentioned… It is the story of consciousness on its dramatic journey through this eternal world cycle.”[17]. In other words, every 5,000 years the cosmic clock resets. Importantly, this cycle is said to be eternal – it has no absolute beginning or end, but continuously repeats[17].

From this viewpoint, the assumptions in modern cosmology find a different context. If our universe is indeed in one 5,000-year cycle, then the light we see from all across the cosmos may merely depict events within this cycle. Time is not infinite into the past or future but wraps around; once a cycle completes, the “Time Wheel” returns to its starting point and entropy resets to zero[19]. As one BK text explains: “the events of the world are not linear and… when the Time Wheel, having completed one cycle, takes the turn of the position from where it started, then… the Entropy would be restored to zero.”[19]. In effect, what science interprets as billions of years might be seen by BK adherents as a grand illusion created by cyclic time.

Furthermore, BK teachings emphasize that consciousness transcends physical speed limits. They note that “according to Physics, the speed of light is the ultimate… but the speed of Thought is very much higher so that it cannot be measured”[20]. In their philosophy, thoughts travel instantly to the distant past or future, whereas light must physically traverse space. This suggests a worldview where spiritual awareness or divine vision is not constrained by light speed. Thus, from the BK angle, even if we only physically see stars that sent light eons ago, our soul’s consciousness might directly perceive the true “present” of all things within the cycle.

Putting this together, one can argue the following: since scientific measurements of cosmic age hinge on assumptions (constant c, inertial frames, linear time) that can’t be proven, there is philosophical room for an alternate scenario. In that scenario, the universe’s entire observable expanse could correspond to just 5,000 years of actual history – the current cycle. The light from distant galaxies would then be part of this cycle, and we simply see them as they were in the past portion of our cycle. What appears to be the distant past (millions or billions of years) is, in this view, a “time lag” within the single drama of one cycle.

In practical terms, proponents suggest that the immense speed of light and its bending by gravity mean our interpretation of “distant past” might be misleading. For example, if light is lensed or time is cyclic, then distant starlight might have originated at a point in our cycle rather than from a time billions of years ago. While this idea lies outside mainstream science, it is not strictly disproven by any experiment – it relies on philosophical choices about time. Indeed, mainstream physics itself includes mysterious, untested assumptions (flatness of space at extreme scales, nature of dark energy, etc.) that could in principle allow for nonstandard interpretations.

Conclusion: A Synthesis of Science and Philosophy

In summary, modern science’s picture of light and time is based on elegant but partly untestable assumptions. Light’s constant speed and our frame choices let us measure cosmic distances and age, but these are assumptions that structure our understanding. Experiments like Michelson–Morley showed that light’s round-trip speed is constant[9][8], but the one-way constancy is essentially a convention[4]. Gravity further complicates things by bending light paths[11]. Meanwhile, cutting-edge questions (quantum gravity, inflation, VSL) show that fundamental aspects of space-time are still not settled[13][15].

Viewed through a Brahma Kumaris lens, these scientific unknowns are compatible with a cyclic universe of 5,000 years[17][18]. If the cosmic clock resets every cycle, then every observation we make of light from galaxies fits within that single drama. As BK teachings say, “Time is cyclic” and when a cycle completes “entropy would be restored to zero”[19]. Within this worldview, the finite and potentially variable journey of light means we may only be glimpsing the current cycle. hence, It will be prudent to universe’s true timeline is measured in cycles, not years.

This synthesis is respectful and philosophical: it does not dismiss science, but highlights that where science reaches interpretive limits, a spiritual perspective can offer a different understanding. The Brahma Kumaris teachings provide an example of such a perspective. According to their tradition, the universe is akin to a grand stage performing a 5,000-year cyclic play[17][18]. In this play, what we see through telescopes could be just the scenery of the current act. Whether one takes this literally or metaphorically, it shows one way to reconcile the mystery of light and time with a belief in an ordered, cyclical cosmic plan – a plan described in their philosophy as the greatest story ever told[17].

Sources: Established physics references (NASA, Wikipedia, scholarly analyses) document how light’s speed and relativity are treated experimentally[1][4][9][8][13]. These highlight the assumptions and unresolved issues. Brahma Kumaris sources describe the 5,000-year cycle and cyclic time wheel[17][18][19][20]. All citations appear above in bracketed format.

[1] [2] Speed of light – Wikipedia

[3] [6] [12] SCALE AND DISTANCE

[4] [7] One-way speed of light – Wikipedia

[5] [10] Michelson–Morley experiment – Wikipedia

[8] [9] The Explanation of the Michelson-Morley Experiment Results by Means Universal Frame of Reference

[11] Black Holes – NASA Science

[13] [14] [15] List of unsolved problems in physics – Wikipedia

[16] Variable speed of light – Wikipedia

[17] World Drama Cycle » Brahma Kumaris

[18] belief – Is the “Mahayuga (i.e., 4 Yugas) lasting for only 5000 years” theology of Brahma-Kumaris found in any scriptures? – Hinduism Stack Exchange

[19] [20] Chapter – 5 Do You Know Your Real Self » Brahma Kumaris

Leave a Reply