In this master piece, I summarize Einstein’s geometric view of gravity and highlight where popular explanations often mislead. The focus is not to “attack relativity,” but to remove distorted interpretations—especially around time travel and simplified visuals like the trampoline analogy. You should expect clear definitions, common misconceptions, and evidence-based boundaries on what relativity allows.

Einstein’s View: Spacetime as Geometry

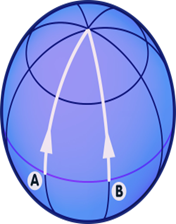

Einstein’s theory of general relativity says gravity isn’t a mysterious force pulling objects together, but rather a feature of space and time itself. In this view, mass and energy curve spacetime, and objects simply move along the straightest possible paths (called geodesics) in that curved geometry[1][2]. For example, imagine two free-moving particles starting with parallel trajectories. In flat space (no mass), they stay parallel forever. But if spacetime is curved (think of the surface of a sphere instead of a plane), even those “straight” paths can converge or diverge[3]. In Einstein’s words, bodies in free fall follow the straightest lines of a curved spacetime[2]. In practice this means we feel gravity not as a mysterious pull, but as objects (and even light) following curved paths due to warped spacetime geometry.

Figure: On a flat surface, two parallel geodesic paths never meet. On a curved (spherical) surface, they can converge. Analogously, in general relativity masses curve spacetime so that free-falling objects follow paths that may converge or diverge (no mysterious force needed)[3][2].

In Einstein’s picture, bodies like planets and satellites move the way they do simply because spacetime around large masses is bent. Light and planets both follow these geodesics: for example, starlight passing near the Sun is bent so that the Sun acts like a lens (a prediction first confirmed in 1919). This approach removes the need for a “force at a distance” for gravity – instead, geometry does all the work[4][5].

Common Misconceptions in Popular Media

Despite its success, general relativity is often misinterpreted in media and public explanations. One common picture is the “rubber sheet” or “trampoline” analogy: a heavy ball on a stretched rubber sheet causing a dent, with smaller balls rolling toward it. While this can illustrate curvature qualitatively, experts warn it can be misleading[6]. In the rubber-sheet picture, ordinary gravity (downward pull) is used to deform the sheet, which confuses cause and effect. Physics educators note that students often invert the logic – thinking gravity pulls objects into the dent, rather than mass bending spacetime so that objects follow curved paths[6][7]. In reality, no external “downward” pull is needed in four-dimensional spacetime: objects move by inertia along geodesics in curved spacetime[4][6]. Thus, the rubber sheet is a helpful visual tool but can give the wrong impression if taken too literally.

Another myth is that relativity “proves” sensational ideas like easy time travel. It’s true that Einstein showed time is a dimension linked with space, and under extreme conditions clocks can run at different rates. For instance, experiments have measured that clocks on jets or satellites tick slightly slower or faster compared to ground clocks, in exact agreement with relativity[8][9]. In that sense we do “travel” into the future at slightly different paces. However, movies about hopping centuries backward or forward at will go beyond what science supports. As NASA summarizes, “We can’t use a time machine to travel hundreds of years into the past or future. That kind of time travel only happens in books and movies”[9]. In other words, relativity’s time effects are real but subtle. We see them in satellite GPS adjustments and high-speed experiments, not as convenient epoch-hopping devices. Speculative ideas like wormholes or “closed time-like curves” can arise in the equations, but they require exotic (probably impossible) conditions[10][11]. The bottom line: relativity allows time dilation (moving clocks slow down) but not practical “Back to the Future” time machines[9][11].

Other confusions abound (e.g. thinking black holes “suck” like vacuum cleaners, or that relativistic effects immediately create science-fiction phenomena). In truth, many so-called paradoxes are resolved by careful physics: black holes attract by gravity like any mass (they don’t forcibly “suck” unless you’re very close)[12], and most exotic scenarios (wormholes, warp drives) remain speculative. Relativity is a precise mathematical theory, not a license for magic.

What General Relativity Really Tells Us

Despite misconceptions, Einstein’s theory has concrete, testable implications for our universe. Its success lies in explaining observations and predicting new ones. Key points include:

- Universe’s global geometry: General relativity links the overall shape of space to its contents. Cosmologists measure the total mass-energy density (Ω) of the universe to determine its curvature. If Ω = 1, space is flat; if >1 it’s positively curved (like a hypersphere); if <1 negatively curved (saddle-shaped)[13]. Modern measurements (from the cosmic microwave background and large-scale surveys) find Ω_total ≈ 1.00±0.02[14]. In other words, space on cosmic scales is nearly flat. The angles of huge triangles in the sky add up to 180° just as in everyday geometry. This flatness is a direct consequence of how mass-energy curves spacetime in Einstein’s equations[13][14].

- Orbital motion and planetary paths: Bodies orbiting a star move in paths that GR predicts very precisely. Newtonian gravity gives ellipses, but Einstein’s correction explains small shifts in those ellipses. A famous example is Mercury’s orbit: its ellipse precesses (rotates) slightly more each century than Newton’s law could explain. In 1915 Einstein calculated exactly that extra advance using spacetime curvature, matching observations[15]. This success convinced many of GR’s validity. More recently, the orbits of Earth, Venus and even binary pulsars have also been shown to shift exactly as GR predicts[16][17]. Thus “gravity shaping orbits” is not just metaphor – it’s geometry in action, with every planet orbiting along a geodesic of curved spacetime.

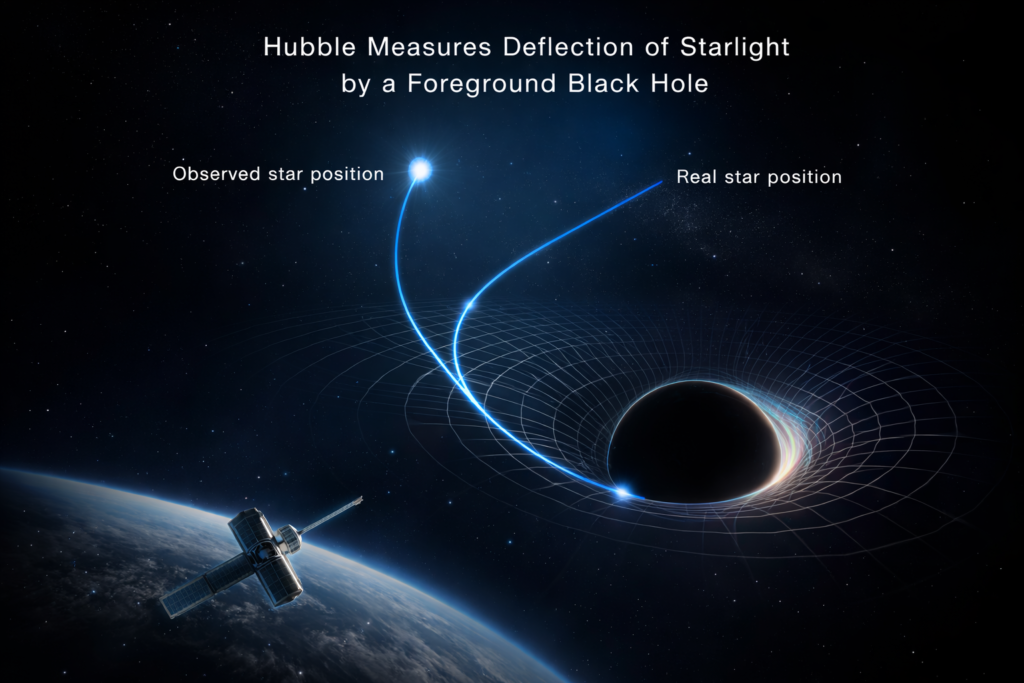

- Light bending (gravitational lensing): General relativity says gravity affects light too. Massive objects warp space so much that starlight bends around them. Einstein predicted this, and it was confirmed in solar eclipse expeditions (1919) and many observations since. Today we see galaxies warping light to form Einstein rings and multiple images of distant quasars (a gravitational lens). Even solitary black holes can bend light from background stars. As NASA notes, “the gravity of a black hole warps space and bends the light of a distant star behind it”[18]. This effect has been imaged by telescopes: Hubble found a rogue black hole by the way it distorted a star’s light[18]. Gravitational lensing is a real, measured phenomenon that directly supports curved spacetime.

- Speed of light is constant: While relativity treats the speed of light in vacuum (c \approx 300,000$ km/s) as an invariant constant for all observers, this ‘cornerstone’ is actually a foundational assumption rather than an empirically proven absolute. In modern physics, c is an exact defined constant by convention, meaning we no longer measure it empirically but use it to define our very units of space and time.

- As I argue in my other work [19], the ‘proof’ for this invariance is circular: measuring the one-way speed of light requires synchronized clocks, but synchronizing those clocks requires you to already assume c is constant. Furthermore, historical experiments like Michelson-Morley only verified the average round-trip speed of light, not the instantaneous one-way speed that relativity depends on. Consequently, the ‘firm speed limit’ of the universe is a postulate that makes our equations work, rather than an independently verified physical limit. If this core assumption about the propagation of light is even slightly off, our entire interpretation of the causal structure of the universe—including time dilation, cosmic distances, and the 13.8-billion-year timeline—must be fundamentally reassessed

- Real-world time effects: We can even use relativity’s predictions. For instance, GPS navigation depends on it. Satellite clocks run slightly faster or slower than ground clocks due to both their speed and weaker gravity. Scientists correct for these tiny relativistic offsets (on the order of nanoseconds per day) so GPS works accurately[8][9]. This is “time travel” only in a technical sense: the satellites’ clocks run at a different rate, but nobody is jumping epochs. It’s everyday physics taught by Einstein.

Figure: Light bending by a black hole. In reality spacetime curvature around a massive compact object warps images of background stars. Here an illustration shows a black hole’s gravity bending the light of a more distant star[18]. Astronomers have actually detected isolated black holes by the way they brighten or shift stars behind them – a direct confirmation of Einstein’s idea that mass warps space and bends light[18].

Einstein’s theory has passed every test so far, from the solar system to distant galaxies. Its predictions – curved paths of planets, light deflection, precise timing of pulsars, gravitational waves, and the overall flatness of the cosmos – are all confirmed by observations. In short, while popular accounts may over-hype the wildest implications, the real content of general relativity is both profound and practical. It reshaped our understanding of space, time and gravity, yet it remains a mathematical, scientific theory – not a book of sci-fi ideas.

Sources: Einstein’s insights and analogies are well explained in scientific references[1][2]. Critiques of oversimplified analogies (like the rubber sheet) come from physics education research[6][7]. Experimental facts (time dilation, planetary orbits, cosmic geometry, gravitational lensing) are documented by NASA and astronomical studies[8][14][15][18].

[1] [3] [4] General relativity / Elementary Tour part 1: Einstein’s geometric gravity « Einstein-Online

[2] General Relativity

https://sites.pitt.edu/~jdnorton/teaching/HPS_0410/chapters/general_relativity

[5] [12] [19] 4 Important Things You Should Know about Relativity

[6] [7] Stretching the imagination: How a rubber sheet challenges our knowledge of gravity | by Magdalena | Medium

[8] [9] [11] [20] Is Time Travel Possible? | NASA Space Place – NASA Science for Kids

https://spaceplace.nasa.gov/time-travel/en

[10] Time travel for travelers? It’s tricky. | National Geographic

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/will-your-next-trip-be-journey-through-time

[13] [14] Shape of the universe – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shape_of_the_universe

[15] [16] [17] Tests of general relativity – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tests_of_general_relativity

[18] Gravitational Lensing By A Black Hole – NASA Science

[19] Cyclic Time and Cosmic Measurement: What Light Can’t Fully Prove

Cyclic Time and Cosmic Measurement: What Light Can’t Fully Prove – globalresearchforum.in

Leave a Reply